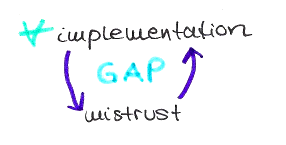

Precarity – the uncertainty over long-term access to resources – is wide-spread in the cultural sector. Low paid or even unpaid work, excessive workloads and low institutional support for freelancers are only some of its characteristics. Even though I originally didn’t come to Bucharest to specifically study working conditions, it soon became a focus of my research – I have written about it here and here. I had been working on precarity issues and collective organizing in Berlin, too, so I was already aware of the problem, and when I started talking to professionals in the cultural sector in Bucharest, it immediately leaped into my view. While the positive effects and products of cultural production are eagerly seized (after all, it is one of the fastest growing sectors in the EU), the people producing them – artists, curators and other art workers – are not sufficiently compensated for their work. This is worrisome, and it is not limited to the cultural sphere – the shift from open-ended full time employment to flexible and less secure working arrangements (part time work, freelancing, unpaid so-called “portfolio work”) is part of the neoliberal restructuring of society. The development is merely more salient in arts and culture. It affects the independent cultural sector exceedingly, because there, most employment options are project-based and many professionals go a long way until they score a salaried position in their discipline. Typically, this path is paved with vast amounts of unpaid work necessary to build up a portfolio for oneself, while resources are scarce and qualified competitors are coming from all sides.

Calea Victoriei

In Romania in particular, this situation has been compounded by the ongoing effects of the financial crisis from which the cultural sector is only slowly recovering. But it is also aggravated by cultural policies that privilege short-term outcomes over long-term infrastructure. This seems to be a global trend, as it comes up in policy discussions all over (as exemplified by this recent article). “Hard infrastructure” (buildings, project spaces, institutions) use up a lot of money and are not deemed remunerative enough, but a question that seems to be missing in the debates is what happens to workers‘ rights and social security when people are forced to go from project to project to find employment.

A misguided definition of what counts as “work” seems to lie at the core of the problem, too. Fixing a car, writing a computer program or advising people on their tax returns is “work”. Making a painting, organizing an exhibition or producing a piece of performance art, on the other hand, ranks somewhere between passion, self-actualization and hobby. People might understand that it is a job, but a common notion is that creative workers are not doing it for the money, but for the sake of art. Many overlook the fact that precarity is not only about a lack of money, it is about social security that is attached to the money issue, but also goes beyond it (for example, freelancers might get on well on a month-to-month basis, but the lack of salaried employment prevents them from accruing enough retirement benefits). Social security – understood as a wide principle – is so fundamental that it is simply not acceptable that some people have it and some people don’t. It shouldn’t be a meritocracy, either, a reward for good or a lot of work. You shouldn’t even have to work for it. Instead, it should be the premise that everyone builds their life on.

The National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, Parliament Building

While we are far from a society where this is a lived reality, I believe that there are some policy measures that can reduce precarity within the given conditions. This is why I have spent a portion of my project on drafting a policy brief calling for policy makers to take anti-precarity measures into consideration. It contains facts that I gathered about precarity in the cultural sector in Romania, arguments about why policy makers should tackle the problem, as well as policy recommendations. It is the snap-shot of a work-in-progress that I hope to continue in the future, and I hope that by sharing it I can contribute to the debate.

Seizing the artwork, neglecting the artist? A call for policy makers to tackle precarity in the cultural sector [PDF]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The brief focuses on culture professionals, but since precarity does not only affect them, it seems important to think about alliances with precarious workers across sectors, too. This perspective unfortunately went beyond the scope of this project.

I’m not the first one to explore and care about this topic, too. So for everyone who wants to dig deeper into the issue, I have compiled a list of the resources that I consulted during my project (see below). But the most important resource that has informed the policy brief were the interviews I conducted with culture professionals in Bucharest.

The websites of ArtLeaks, a collective platform committed to publicize and fight abuses of labor rights in the cultural sphere, and Cultural Workers Organize, a research project on precarity in the cultural field, each offer an extensive list of resources, too.

This list is certainly not exclusive, so feel free to share your recommendations in the comments!

![[PHOTO]](https://practicetopolicy.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/2016-04-27-19-17-06.jpg?w=450)

![[PHOTO]](https://practicetopolicy.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/2016-04-27-10-09-46.jpg?w=225&h=300) The concept was simple: with a map in hand, you walked around town and visited galleries for free. The first thing I observed was just how many galleries there were – the map was extensive! In the end, I was only able to cover four of them. The spaces weren’t crowded – often, there were only three or four other people with me in the mostly smaller exhibitions. But considering that there were so many offers simultaneously and that I saw several people walking on the street with the same map in their hands, the interest in these types of events seems to be big. I’ve learned that this information is important from a public policy perspective: You need to know the audience for specific cultural activities.

The concept was simple: with a map in hand, you walked around town and visited galleries for free. The first thing I observed was just how many galleries there were – the map was extensive! In the end, I was only able to cover four of them. The spaces weren’t crowded – often, there were only three or four other people with me in the mostly smaller exhibitions. But considering that there were so many offers simultaneously and that I saw several people walking on the street with the same map in their hands, the interest in these types of events seems to be big. I’ve learned that this information is important from a public policy perspective: You need to know the audience for specific cultural activities.![[PHOTO]](https://practicetopolicy.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/2016-04-27-10-12-33.jpg?w=300&h=225)